The Economy of the Byzantine Empire

Despite its struggles for most of its history the Byzantine Empire remained a firm economic powerhouse. It had a strong agricultural and trade based economy. It inherited an already powerful place infrastructure, leadership and military from the old Roman Empire. This provided a solid economic foundation for them to dominate the a big chunk of the Mediterranean Basin.

Where the economic history of Byzantium is concerned, the phenomenon of the cities of the empire is of great significance, not simply because it was there, as I have noted in the, that secondary and tertiary production developed, but also because the cities are bound up with questions of demography, spatial planning and the distribution and consumption of products.

Most of the trade happening throughout empire came from sea-links and ports tied to the Mediterranean Basin. The new capital allowed the imperial government to overlook surrounding empires and because the eastern side of the Roman Empire was more successful and wealthier after the fall. Constantinople became the most important center for political and military affairs for the Eastern Roman Empire and became dominant economic and commercial center in the Eastern Mediterranean. The Eastern half remained completely intact with roads, communication and authority. The Eastern Roman Empire was always richer and much more developed than the Western one, though it had less potential of further growth. Minor Asia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt had agricultural economies that were well established and as such they had little room for further development but nonetheless they were fertile and prosperous. They provided the bulk of state revenues and it should be mentioned the entirety of Egypt alone must have provided 30% to 40% of the byzantine budget according to estimates.

Taxation, which was heavier on the countryside, led many people from rural areas to move to the major cities of the Empire, which as such saw a big population growth. Constantinople saw an explosive growth, benefiting from its status as an imperial capital, and by the estimtes of some byzantine chronicles, in 450, it had a population of around 190.000 people. Other major cities included Alexandria, Antioch and Thessaloniki. The Empire had about nine hundred places with the legal status of cities but most of them were really just in towns, with average size of one thousand inhabitants. Those cities were the economic centers of the Empire as they were responsible for tax collection.

The tax collection from the countryside for the reimbursements of the expanded state machinery of army and imperial bureaucrats increased trade in cities that served as administrative centers and also benefited outlying territories where border armies were stationed. As the majority of easterners lived near the sea, this facilitated trade as moving goods through sea and rivers was much cheaper than land transportation.

Between the time of Diocletian to the time of Marcian (284–457), the byzantine state established its long-lasting institutions. The expansion of the bureaucracy and army by Diocletian and Constantine were accompanied by an expansion of taxes and an improvement of the tax-collecting abilities of the state; Diocletian introduced a new system of taxation based on heads (capita) and land (iugera). The reform was effected in Egypt and presumably in the whole Roman Empire, in the year 297, as shown by an Edict of Aristides Optatus, prefect of Egypt. Runaway inflation had been a major problem for the empire since the crisis of the third century. Diocletian attempted to solve this problem by trying to reestablish trustworthy minting of silver and bullion coins but his attempts ended up in failure. Constantine, instead of trying to restore the silver currency, concentrated on minting large quantities of good standard gold pieces, the Solidus or Nomisma. Solidus has been called the "dollar of the Middle Ages" and was highly valued in Western Europe. Its value remained largely stable until the crisis of the eleventh century and the devaluations of that period. A large part of Byzantium’s prosperity thus was a result of Constantine’s monetary reform.

The period of the late 10th and first half of the 11th century was the second peak of Byzantium’s economic and political power, afterthe 6th century peak under Justinian. Politically Eastern Roman Empire stretched almost as far as it did under Justinian. It controlled all of Anatolia, parts of the Middle East, the south

of the Crimea, the Balkans, and Southern Italy. It thus stretched from Bari in the West to the Caucasus in the East, from Cherson in the Crimea to Antioch in the Middle East. The territories that were lost compared to the Justinian’s Byzantium were Northern Africa (including Egypt) and Southern Spain, Northern Italy, parts

of Sicily, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. Its estimated population was between 12 and 18 million. This is also the period that coincided with a strong rule of Basil II (976–1025),

a key emperor of the Macedonian dynasty. Basil II was able to simultaneously roll back the Eastern advances of the Turks, and to recapture Bulgaria and reintegrate the Balkans into Byzantium. He was also able to hold at bay attempts by the Normans to take over Southern Italy and control the Adriatic. He was thus victorious on the three fronts, the very fronts from which the danger was about to continue and in the second part of the 11th century after disastrous losses in 1071 against the Seljuqs at Manzikert and Normans in Bari—lead to the gradual weakening and shrinking of the Empire.

Painting depicting a byzantine peasant farming

The power of the Byzantine Empire’s early economy was largely predicated upon the land. Anatolia, the Levant, and Egypt were well developed agricultural regions which yielded huge amounts of tax revenues for the state. Some estimate that Egypt alone may have contributed up to 30% of the annual tax take. The climate across the empire was excellent for various types of farming activity. In coastal areas cereal crops, vines and olives were produced in vast quantities, whereas interior areas were mainly given over to raising livestock of various kinds. Fruits and vegetables were also widely produced, including in urban centers and there were large sections of Constantinople given over to gardening.

Agricultural production was based around the village. Villages were occupied by a variety of inhabitants, many of them landholding farmers who owned their land and therefore paid taxes directly to the state. Gradually, this system was replaced by a network of large estates worked by a mixture of slaves, wage laborers and tenant farmers.

From the 10th century, the concentration of land in the hands of fewer and fewer powerful noble families accelerated, and successive emperors passed a series of land laws attempting to prevent the alienation of land from small landholding farmers. Despite this legislation, by the high middle ages, the rural landscape of Byzantium had changed completely. The patchwork of small villages that had previously made up the agricultural economy had been almost entirely replaced by large estates.

These powerful landowning families (particularly concentrated in Anatolia) represented a political threat to the imperial crown in Constantinople, as they were essentially self-sufficient, with their own tenants and retinues. For example, Bardas Skleros, Byzantine general and member of the Skleroi family who held vast estates in the east led a revolt against Basil II that lasted from 976-79.

Aside from agriculture, trade was an important element of the Byzantine economy. Constantinople was positioned along both the east-west and north-south trade routes, and the Byzantines took advantage of this by taxing imports and exports at a 10% rate. Grain was a key import, particularly after the Arab conquests of Egypt and the Levant meant the empire lost its primary sources of grain.

Silk was also an important Byzantine import, as it was crucial to the state for diplomatic and prestigious purposes. However, after silkworms were smuggled into the empire from China, the Byzantines developed their own silk industry and no longer had to rely on foreign supplies.

Various other commodities were also traded, both internally within the empire, and internationally beyond its borders. Oil, wine, salt, fish, meat and other foods were all traded, as were materials such as timber and wax. Manufactured items such as ceramics, linens and cloth were also exchanged, as well as luxuries such as spices, silks and perfumes.

Trade was also important to Byzantine diplomacy. Through maintaining trade relations, the Byzantines could bring various peoples and nations into their sphere of influence and potentially use them in regional alliances. Bulgarian and Russian merchants brought wax, honey, furs and linen, while hides and wax were purchased from the Pechenegs, a nomadic people who lived north of the Black Sea in the 10th century. Spices and manufactured goods entered the empire from the east, usually in trade caravans that passed through the cities of Anatolia. Venice was also a trading partner, and by 992 Venetian naval power was considerable enough to warrant Venetian merchants being granted a reduction in customs duties in Constantinople.

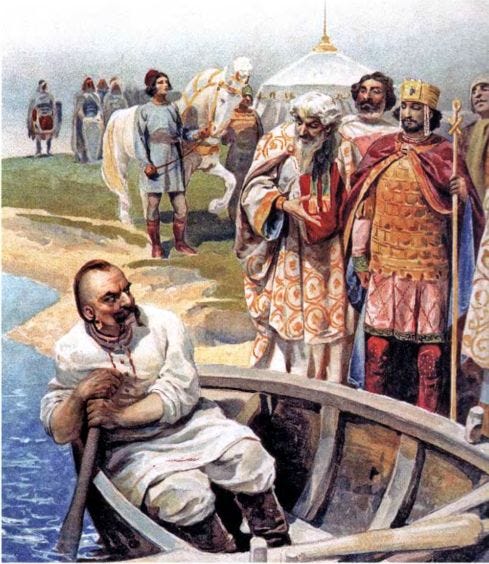

Painting of a Kievian Rus merchant and the byzantine emperor

The state held a monopoly on coinage and intervened in the economy in various ways. It controlled interest rates and carefully orchestrated economic activity in Constantinople, setting stringent regulations for the city’s guilds to follow (which can be seen in the 10th century text, the Book of the Eparch). The state also intervened to ensure that the capital was provisioned with grain and to drive down the cost of bread. Riots could occur that threatened the emperor’s reign if food was not cheap and readily available in Constantinople.

Despite the upheaval of the early medieval period, the Byzantine Empire still maintained a wide-reaching bureaucracy and powerful state mechanisms, which allowed it to have standing armies and effective tax collection. As it was so large, the state also created a huge amount of economic demand, meaning market forces had little effect on the Byzantine economy. Soldiers and bureaucrats were paid in gold coin, which they used to purchase goods, ensuring coinage was effectively recycled through the economy and ended up back in the hands of the state through taxation of the peasantry and rural elite.

From the 10th until the 12th century, Byzantium enjoyed considerable economic prosperity, with annual revenues in 1025 standing at 5.9 million nomismata, and a treasury reserve of 14.4 million. This wealth allowed the Byzantine empire and its emperors to project an image of their power abroad, increasing their own prestige. Visitors to Constantinople, such as the Italian diplomat Liutprand of Cremona, were impressed by the luxurious imperial palaces and incredible riches that they witnessed in the city. However, this economic success was not to last.

Several factors contributed to the terminal decline of the Byzantine economy, the greatest among which was undoubtedly the fourth crusade. Beginning in 1202, the crusaders had originally intended to attack Jerusalem via Egypt but ended up encountering financial issues that saw them attack the city of Zara on the Adriatic. On the route to Jerusalem, they entered into an agreement to aid the Byzantine prince Alexios Angelos in restoring his father Issac II to the Byzantine throne, in return for military and financial aid.

In 1204, when the newly crowned co-emperor Alexios was overthrown by a mob in Constantinople, the crusaders simply decided to conquer the city. What followed was the brutal sack of Constantinople in April 1204. For three days the crusaders looted and vandalized the great city, stealing much of the vast wealth that had been accumulated over many centuries. Ancient Greek and Roman works were taken or else destroyed (the famous bronze horses from the Hippodrome were taken back to Venice and now decorate St. Mark’s Basilica there), and Constantinople’s churches were systematically plundered. The human cost was enormous too, with many thousands of civilians being massacred in cold blood.

The crusaders left a gutted and destroyed city behind it is estimated that Constantinople was looted of some 3.6 million hyperpyra (the currency that had replaced the nomismata). The crusader leaders divided the empire amongst themselves into what became known as the Latin Empire, while the Byzantines were left with three successor states: The Empire of Nicea, the Despotate of Epirus, and the Empire of Trebizond. The Nicean Empire lost a great deal of territory in southern Anatolia to the Sultanate of Rum, and by the time it recaptured Constantinople from the Latins in 1261 and reestablished the Byzantine Empire, it was ravaged by warfare.

Subsequent emperors attempted to expand the empire and restore some of its former glory but were hampered by a shattered economy. A reliance on harsh taxation angered the peasantry and the use of mercenary troops proved to be unreliable and ineffective. From the mid 14th century until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the empire slowly lost territory to Serbian and Ottoman aggressors. It is estimated that in 1321 the annual state revenue stood at just 1 million hyperpyra.

By the time of the siege in 1453, the once great Byzantine Empire effectively consisted only of territory on the European side of the Bosporus surrounding Constantinople. The city itself was hugely underpopulated and in a state of extreme disrepair.