The Kamakura Shogunate

Introduction into it’s history

Map showing the maximum extent of the Kamakura Shogunate

Kamakura is one of the coastal towns located on Sagami Bay on Honshu Island, Japan, which was for a time the capital of the Kamakura Shogunate from 1192 to 1333. Provided with strong natural defensive features, it was fortified and made the base of the Minamoto and then the Hojo shoguns. Several important buddhist temples were built at the site such as the Kenchoji Temple, and there still remains today the massive bronze Buddha that once belonged to the Kotokuin Temple. The city itself fell toghether with the Kamakura Shogunate when it was attacked by an army of rebel samurai led by Nitta Yoshisada in 1333.

Kamakura is located 48 kilometres southwest of Tokyo (also known known as Edo during Medieval Japan) on the east coast of Honshu Island in the Kanagawa Prefecture. It was nothing more than a village for fisherman before it was given a new strategical role in the medieval period, although the Kojiki, Japan's oldest historical book compiled in 712, does make a brief mention of the Lords of Kamakura. Kamakura really rose to fame when it was used as the base for the powerful Minamoto Clan which dominated Japan in the last quarter of the 12th century until the first quarter of the 13th century when they were superseded by the Hojo Clan. Even then, it continued to be the capital of the shoguns (most of them former emperors turned into military autocrats) for another century or so.

Minamoto no Yoritomo, shogun of Japan from 1192-1199 and founder of the Kamakura Shogunate (1192-1333) selected Kamakura as a safe place for his new capital in 1192. The site was well protected by mountains on three sides and the sea on the fourth side. A large tunnel was excavated through the relatively soft rock, the Shakado tunnel, which provided a handy escape through the mountains if required. Ever wary of a rival warlord or rebellion in the militaristic political landscape of medieval Japan, Yoritomo ensured Kamakura was given much more protection than nature provided. First, the mountains behind the city were further fortified with a long series of earthworks defensive walls. Next, two wooden stockade castles were added: Sugimoto and Sumiyoshi. Sugimoto was built right in the heart of Kamakura while Sumiyoshi was erected at the eastern end of the beach. The only other thing needed was to carve out more open space for the enlarged city, a process that caused much deforestation in the area.

Statue of Minamoto no Yorimoto, the first shogun of Japan

The first Shogun

In 1180, the son of cloistered Emperor Go-Shirakawa, Prince Mochihito, was disgraced by the Taira clan for their support in the accession of the throne of his nephew and half Taira, Emperor Antoku. Prince Mochihito made a national call to arms of the Minamoto clan all over Japan to rebel against the Taira. Yoritomo joined this effort and set himself up as the rightful heir of the Minamoto clan and built a capital in Kamakura.

When Taira no Kiyomori died, a far harsher Taira no Munemori took his place. He set much more aggressive policies against the Minamoto during the Genpei War. Yoritomo however was secured at Kamakura and his brothers Monamoto no Yoshitsune and Monamoto no Noriyori defeated the Taira in several important battles.

From 1181 to 1184, a de facto truce with the Taira allowed Yoritomo time to build an administration of his own which centered on his military headquarters in Kamakura. Finally, Yorimoto defeated his rival cousins from stealing from him his stronghold on his clan.

Minamoto no Yorimoto established the supremacy of the warrior samurai caste and the first shogunate (bafuku) at Kamakura. This was the beginning of the feudal age in Japan that lasted until the mid 19 century.

Yoritomo’s legacy is said to include the Throne “handed to the leader of the military class effective jurisdiction in matters of land tenure and the income derived from agriculture”. This was made possible by Go-Shirakawa in December of 1185, by giving Yoritomo the authority to collect the levy contribution of rice and to appoint stewards (jito) and constables (shugo).

Yorimoto further established his power by invading and subjugating the provinces of Dewa and Mutsu. He also took up formal residence in the Rokuhara mansion at the capital, Taira clan’s former headquarters.

When Go-Shirakawa passed in 1192, his successor, Go-Toba made Yoritomo Sei-i Tai Shōgun. This made possible the organization of a feudal state in Kamakura while Kyoto became just a place for “national ceremony and ritual”.

Upon Yoritomo’s death, his wife’s family, the Hōjō, took control and maintained power over the shogunate until 1333, under the title shikken (regent to the shōgun). The stone pagoda gorintō is traditionally believed to be Yorimoto’s grave.

Why is this Shogunate so important for the history of Japan?

The Kamakura shogunate was the first of three shognuates that managed to create a central governmental structure in Japan. This first shogunate left much intact from the preceding Imperial Period during the Medieval Era of Japan, including tax structures and the system of “shoen” or private enterprises, making it one of the first states in medieval history to form a proto-corporatist system. The “Bakufu” was a rather small government, with only three offices: one administering and enforcing shogunate policy, one overseeing shogunal retainers, and one which dealt with judicial matters. Shoen holders continued to enjoy their tax exemptions, collecting and keeping taxes within their own lands, and taxes likewise continued to be collected in much the same way as they had been under the Heian court, with a portion of the taxes going to the shogunate and its retainers, and the remainder going to the Imperial Court. Shogunal retainers are believed to have numbered only around 2,500 in the period from 1185-1221 and around 3,000 afterwards. The total population of the archipelago under this whole system is estimated to have been around 10 million in 1300.

The Imperial Court retained a lot of power during this period, with some historians describing the Kamakura period as one of dual governance. While the shogunate appointed military governors (shugo), and stewards (jito) in the provinces, The Imperial Court continued to appoint civil governors such as the kokushi, who also worked to govern these regions and to collect taxes. The Court also continued to exercise more direct control over the areas around Kyoto. Powerful Buddhist temples, retired emperors, and court nobles also continued to wield considerable wealth and influence, some of the becoming shoguns themselves.

Following Yoritomo's death in 1199, his father eized power over the shogunate, by establishing a hereditary claim on the position of shogunal regent, also known as shikken. Yoritomo was succeeded as shogun by his son. For the remainder of the Kamakura period, members of the court aristocracy, or imperial princes, served as shoguns.

During this time, was not uncommon for women in samurai families to be trained in archery and other martial arts, and to enjoy considerable legal rights on a par with men, including the ability to inherit and own property; in a few cases, women even inherited formal titles and posts. As the importance of military service and warrior mentality more generally gained strength, however, women began to lose such legal privileges, and began to be pushed into a more domestic role. As the size and strength of a family's land holdings became more important, the practice of dividing one's land among all of one's sons and daughters was replaced with the practice of male primogeniture, in which the eldest son (or son-in-law, adopted as heir) inherited all.

The shogunate successfully suppressed an imperial complot to ovethrow it during 1221 but was significantly weakened in the wake of two failed attempts by the Mongols to invade Japan. In the fifth lunar month of 1221, the Retired Emperor Go-Toba decided on lines of succession, without consulting the shogunate. He then invited a great number of potential allies from amongst the eastern warriors of Kyoto to a great festival, thus revealing the loyalties of those who rejected the invitation. One important officer revealed his loyalty to the shogunate by doing so, and was killed. Several days later, the Imperial Court declared Hojo Yoshitoki the regent and representative of the shogunate, to be an outlaw, and three days later the entirety of eastern Japan had officially risen in rebellion.

Hôjô Yoshitoki decided to launch an offensive against Go-Toba's forces in Kyoto, using much the same three-pronged strategy as was employed a few decades earlier. One came from the mountains, one from the north, and the third, commanded by Yoshitoki's son Yasutoki. These forces faced meager opposition on their way to the capital; the Imperial commanders were simply outfought. When Go-Toba heard of this string of defeats, he left the city and asked for help from sohei the warrior monks of Mount Hiei. They declined, citing weakness, and the Go-Toba returned to Kyoto. The remnants of the Imperial army fought their final stand at the bridge over the river Uji, where the opening battle of the Genpei War had been fought, 41 years earlier. Yasutoki's cavalry pushed through, scattering the Imperial forces, and pressed on to Kyoto.

The capital was taken by the shogun's forces, and Go-Toba's rebellion was put to an end. Go-Toba was banished to the Islands of Oki, from where he never returned.

The Kamakura period came to an end as the forces of Emperor Go-Daigo rose up against the shogunate, attracting many of the shogunate's own vassals to the Emperor's side and putting an end to Hôjô rule in 1333.

Law and Class Privileges in Kamakura Japan

The Emperor Godaigo Dreams of Ghosts 後醍醐天皇

Subordinates of the first Kamakura shogun, Minamoto no Yoritomo, collected taxes. Yoritomo passed laws and appointed people to imperial positions while the emperor in Kyoto remained a figurehead who performed ceremonies and gave Yoritomo sanction for his policies.

Among Yoritomo's descendants, and in the imperial bureaucracy, sons continued to inherit their father's offices. It was their military government that ruled, the bakufu, literally "tent government."

Government by murder survived in the succession dispute that followed Yoritomo's death in 1199. Two of Yoritomo's sons and a grandson were assassinated by another of his sons. Yoritomo's thirty-two year old widow, Hojo Masako, had retired to a Buddhist nunnery but then she took power and became known as the "nun-shogun." She ruled, made and unmade emperors, and presided over the expansion of the land of her family, the Hojo. The Minamoto family and members of the royal family were puppets and hostages of Hojo family rule.

The shoganate had military force to back up his centralized authority, and, by the year 1230, men around the shogun adopted Confucian principles and believed that it suited their position to be familiar with the Chinese classics. They had an idea of what good government should be. They were interested in law and order, and a part of their new law and order was taming unruly warriors. Penalties were imposed on those who were abusive or started fights. Samurai who started fights could lose their estates.

The shogun's constables gained greater civil powers, and the court at Kyoto was obliged to seek Kamakura's approval for all of its actions. While legal practices in Kyoto were still based on 500-year-old Confucian principles, the new code under Hojo rule was a highly legalistic document that stressed the duties of stewards and constables, provided means for settling land disputes and established rules governing inheritances. It was clear and concise in stipulating punishments for violators of its conditions, and it was to remain in effect past the mid-1800s.

Order meant preserving privileges, and, as with other class societies as far back as Hammurabi's at Babylon, penalties were in accord with one's social status.

The economy in the Shogunate

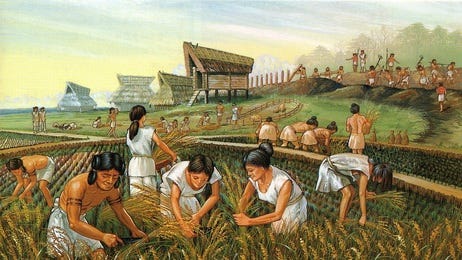

Myoshu (peasants) farming

About half of all the land was in the hands of aristocrat-governors appointed by the emperor's court. The rest of was cultivated by wealthy peasants (myoshu) or controlled by low-ranking warriors. The poor lived scattered in small dark cabins and had a pot, a few bowls and tools such as spades, hoes and sickles. The myoshu lived in a house with a few rooms, a thatch roof, and they owned a few cows, maybe a horse and had more tools. These wealthier peasants rented land to tenant farmers and had farmhands, servants or slaves working for them. They associated their privileged position to the gods and organized Shinto festivals and feasts. The poor were not allowed to organize such gatherings, but they were invited to join in and show their respect.

In mid-1200s, agriculture was advancing in Japan, as it was during the favorable climate that Europe was enjoying. Japan's farmers developed a two-crop system. They flooded their fields in late May or early June to plant rice, which they harvested in October. Then they drained their fields and planted grains. They were making better use of fertilizer. With their greater harvests they participated in an increase in trade. Local markets sprang up near a local lord's manor or perhaps at the gate to a Buddhist temple, or at a crossroads. Poorer peasants began selling soybeans, sesame seeds or string beans and maybe hemp. Better-off peasants sold rice and barley.

With the rise in agricultural productivity and the rise in commerce came a rise in population and growth in the number and size of towns. Traveling merchants joined in, and craft persons were producing more goods for common people, and common people were trading their produce for pottery, farm tools, pots and pans. Craft persons were making umbrellas, leather, saddles, copper products, roof tiles and weaving fabrics. Artisans and merchants traveled more. The number of market days in a locale typically increased from six a year at the beginning of the 1200s to perhaps twenty-one by the end of the century. Rice, lumber, fish, salt, sesame, dyes and other products were being transported about Japan on waterways.

The use of money was increasing. At mid-century, forty or fifty Japanese ships a year arrived at southern China during the reign of the Southern Song and the Japanese exchanged lumber, sulfur and other products for China's copper coins. In the port area where the trade took place, copper coins might follow a visit by Japanese traders. Alarmed, the Song government responded with a decree forbidding the trading of its coins with the Japanese, part of the naiveté of those times about economics. The decree had little effect. Inspectors at China's port took bribes, and coins continued to pass to the Japanese. In Japan the naiveté about money expressed itself in people talking about the new "coin sickness," while authorities in Japan apparently failed to see the benefit in Japan minting its own coins. It was China's money that was respected, along with other things from China.

Good harvests came and went, and those who became destitute sold themselves to slave traders in order to survive. And the slave traders sold them in regions where there was demand for their labor. How easy it was for those who sold themselves into slavery to buy back their freedom is unknown.

The high-ranking lords had vassals who were rewarded with fiefs of their own, and fief holders exercised local policing powers. The lords continued to receive rents from the middle class farmers, the myoshu. Some myoshu might also belong to the samurai class. The myoshu were themselves lords over their tenant farmers, farmhands, servants or slaves, but they differed from the higher lords in that they might work in their fields alongside others. It's a point of disputation among historians whether some who worked for the myoshu could be called serfs or people bound in servitude.

Before the 1200s, there were those who fished on the sea, settled on a beach and then moved on, but in the 1200s they began to settle, to build houses and create villages of fishermen. Their communities tended to be equal, with fishing zones equitably distributed and families heads sharing salt-making ovens. The seashore villages grew into towns, with inns built to house merchants and other itinerants. Two such towns were Tsunuga and Obama (Little Beach), on the northern shore in Western Japan. The independence of such towns ended as the powerful lords or monasteries with the advantages of armed men moved in to claim jurisdiction and the right to tax. They had a protection racket. The towns accepted their power and in return received armed protection against anyone causing them trouble.

Moving through these and other towns were blacksmiths, pot makers, sellers of oil, mats, rice wine and other goods. These itinerants traveled under a freedom accorded them by the imperial court in exchange for their having supplied the court with goods. There were also itinerant dancers and musicians, people who lived by entertaining. Among the dancers and musicians some had a secondary form of entertaining: prostitution. They enjoyed an elevated status and had the same right to travel as the craftsmen and merchants.